“There are a lot of other materials that are interesting, but I think I need 200 more years to create all the stuff I want with wood,” Kraaijeveld says with a laugh. He credits two childhood experiences with his dedication to the material. “I used to live near the coast, and when I was young I would go to the beach after a storm and my dream was to find a piece of wood from a boat that was lost at sea. And the second thing is, I had an aunt in the south of France. Every summer I would go there and after a few days of reading books, there was this urge to create. Her late husband had a large workshop. And the main material found there was wood.”

So what does Kraaijeveld make with all this wood?

“I create realistic mosaics; usually it’s two-dimensional photorealistic work. I started out with cars and household items and now I do a lot of portraits.” But more recently Kraaijeveld took on a somewhat more ambitious project: creating a ten-foot-long, three-dimensional realistic sculpture of Manhattan—made out of wood from Manhattan’s water towers.

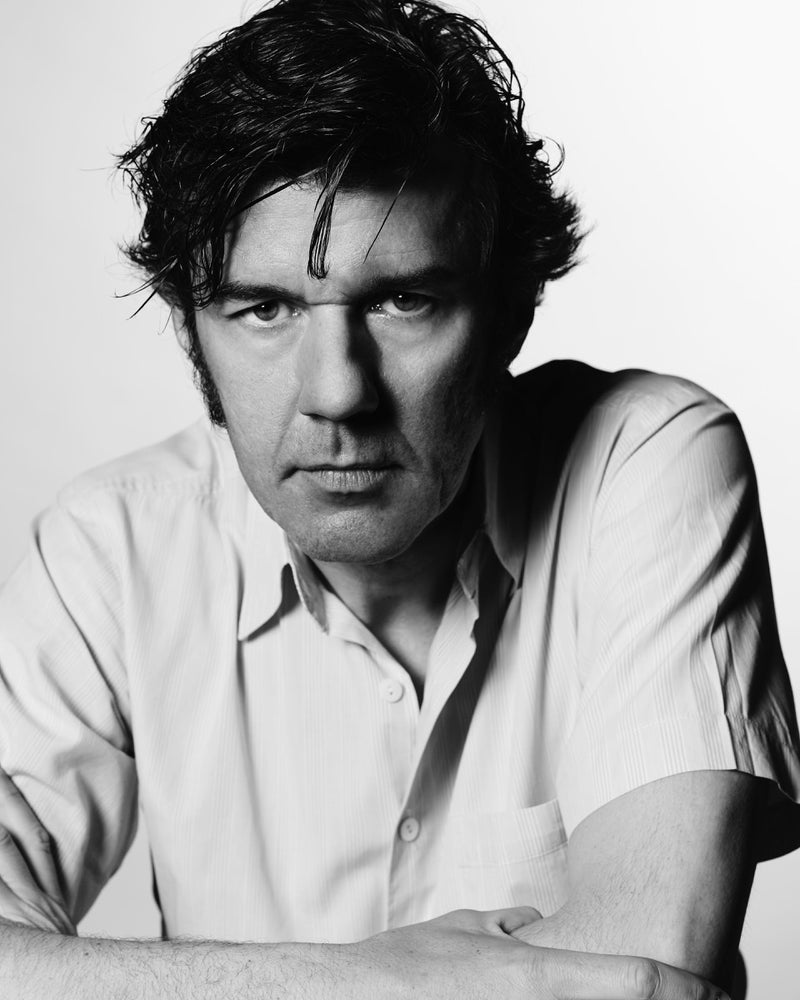

But it’s not as though Kraaijeveld doesn’t have more art to make. He talks about perhaps making an even larger Manhattan, “because when it’s larger, you can add more detail.” He’s also considering making Amsterdam with pieces of old canal houses. And he’s still making his two-dimensional wooden sculptures of objects, as well as of heroes of his, such as famed painter Chuck Close.

“I decided to create some New York icons with New York wood, and he’s a New York artist. And he started out doing really photorealistic portraits, large self-portraits, [which are] amazing. With heroes, sometimes when you talk to them in person, they’re not nice at all, but in this case, he’s not only a great artist, but a great person, too. Maybe you know his famous expression: ‘Inspiration is for amateurs—the rest of us just show up and get to work.’ It’s so true.

We asked Kraaijeveld what other advice he has for young artists. He says, “Even if it doesn’t work out the first time, don’t stop; just go on. And you will see that every time you create something, it gets better. And in the end, you’re the hero.”

Kraaijeveld’s Manhattan will be on display at Dutch Design Week in Eindhoven, Netherlands, this October. When asked if his Manhattan would ever be making an appearance in the real Manhattan, Kraaijeveld says, “I really hope so. That would be great, to have it in Manhattan.”

“I went to New York in the mid ‘80s for the first time to study—and I came back every year since. Everybody from abroad has a picture of New York in his mind, but the first time you go there, it’s overwhelming. I went to Manhattan ten years ago with one of my sons. We took a cab into Manhattan from JFK and we were going over the bridge and I was looking at my son and he was just looking outside of the taxi, looking up, and going ‘Wow.’ And I remembered that feeling I had when I was young; it was so overwhelming and so interesting and so moving. I guess that’s why I have a fascination with Manhattan.

“And of course, there’s the architecture. I love building icons. And the water towers, that’s an iconic image. I was in Manhattan two and a half years ago having a drink with a friend and he said, ‘Diederick, do you realize those iconic water towers are made of wood?’ And I did not know that; I thought they were made of metal. So he gave me the idea: made of wood, it’s iconic, and it’s also historic, those water towers. After about eighty years they are rebuilt, so it’s really old wood; it’s very special wood. So I immediately thought, I need to get some of those beams. And of course, what do you build with wood from Manhattan? You build a Manhattan.”

It took Kraaijeveld about five months to build the giant sculpture, working on it in his studio every single day. “At the beginning, I was a bit worried it would drive me crazy. I was starting in the south, in the Financial District, and that’s a bit of a mess, so to speak—not really straight lines. Then I got to the first street, and I knew I could build one or two streets a day. And I saw it growing every day, and that really made me happy. I really enjoyed working on it. Of course, I was happy when it was finally finished, but it wasn’t the burden I was expecting it to be, actually.”

In fact, Kraaijeveld was somewhat bereft when he’d finished the piece. “On the one hand you’re happy that you’ve finished; you’re proud. But on the other, it’s a bit of—well ‘loss’ is a big word—but you don’t go to the shop to work on it anymore. So it’s a bit sad as well, to finish something.”

.png?v=0)