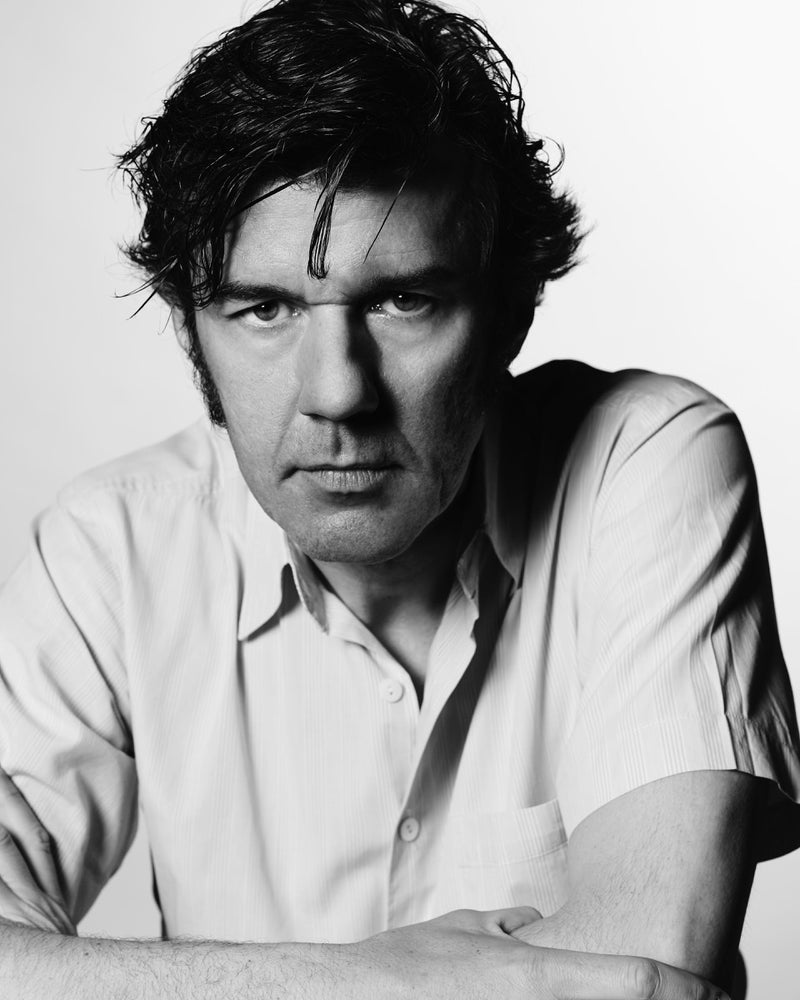

There’s a long history in the United States of Black people’s contributions to different areas of human ingenuity — art, science, invention, and more — being stripped from the record books. But Tamika T. Hall, a journalist-turned-author and mother of six, is doing her part in giving Black creators in the spirits industry their proper due. Through her years of experience covering the spirits industry for publications like stupidDOPE, The Examiner, and her own site LadyBlogga.com, she realized a major problem: Black mixologists weren’t getting their due. If you weren’t deep into history, you’d never know that a Black man, Nearest Green, taught Jack Daniels how to distill whiskey, or that another Black bartender, John Dabney, made the mint julep a household drink. But her upcoming book Black Mixcellence aims to change that, by telling the stories of historic Black mixology pioneers — and also showcasing the genius of present day Black mixologists by presenting their creations. She’s a new author, and works by day as a marketing manager at the edTech company Yellowbrick, but her most important job doesn’t have a barcode or business card. Hall has six children, her youngest in third grade and her oldest an ironworker at Local 40. In honor of Mother’s Day, The 10,000 spoke to Tamika T. Hall about her career, her dedication to chronicling Black mixology, and how she manages motherhood through all of it.

How did you initially get into covering contributions to the spirits industry and spirits culture?

This book initially started as a Black mixology book featuring Black mixologists and their recipes. If you look at the cocktail book space and the recipe book space, we really have minimal representation in terms of books that are published in big bookstores like Barnes & Noble. There are a lot of online books and self-published books, because trying to get these types of books out there is tough. So the idea initially started when Kathy Iandoli introduced me to Kingston Imperial, an independent company who recently acquired a distribution deal with Random House. The idea began to create a book of recipes from Black mixologists, and as we moved through the process, having interviews and speaking to different mixologists, it was a recurring theme that everyone was referring to the Uncle Nearest story. That was the first thing that stuck out in my mind. I knew about him, but I didn’t really know a lot, so I started digging into that. While I was covering a Maker’s Mark event maybe three or four years ago around the Kentucky Derby, the big conversation was a mint julep. Having to do research about the mint julep is when I learned that that, too, was made famous by a Black mixologist. But for me, as it was front-facing, I thought it really started at the Kentucky Derby, because you only hear it in conjunction with the derby. You think that’s where it started, but it’s not. A few Black mixologists had a hand in making that cocktail famous down south, and that’s kind of where it got its legs to become the official drink of the Kentucky Derby. So then I started thinking, I wonder what else we did? What other contributions did we have to push mixology to the forefront?