I step down onto the platform and locate the Amtrak train to Grand Central Terminal. Its metal exterior gleams faintly in the soft daylight, and its hidden engines emit a low drone; hydraulics hiss dramatically as the doors part. The sound is suffused with anticipation, recalling to my mind a dry ice machine as it spurts its atmospheric cloud across an empty, blue-lit stage. I board the train and find a vacant seat by the window. The engines begin to groan, their tireless rumbling rising in intensity as the train eases away.

Daylight floods the carriage. Trees flash past along the bank. The murky mirror of the Hudson River remains beside me; my fellow traveller. Through the Lower Hudson Valley, we journey together in parallel, disappearing occasionally behind pylons or stations before reacquainting ourselves again, fixed on our set paths, flowing southward.

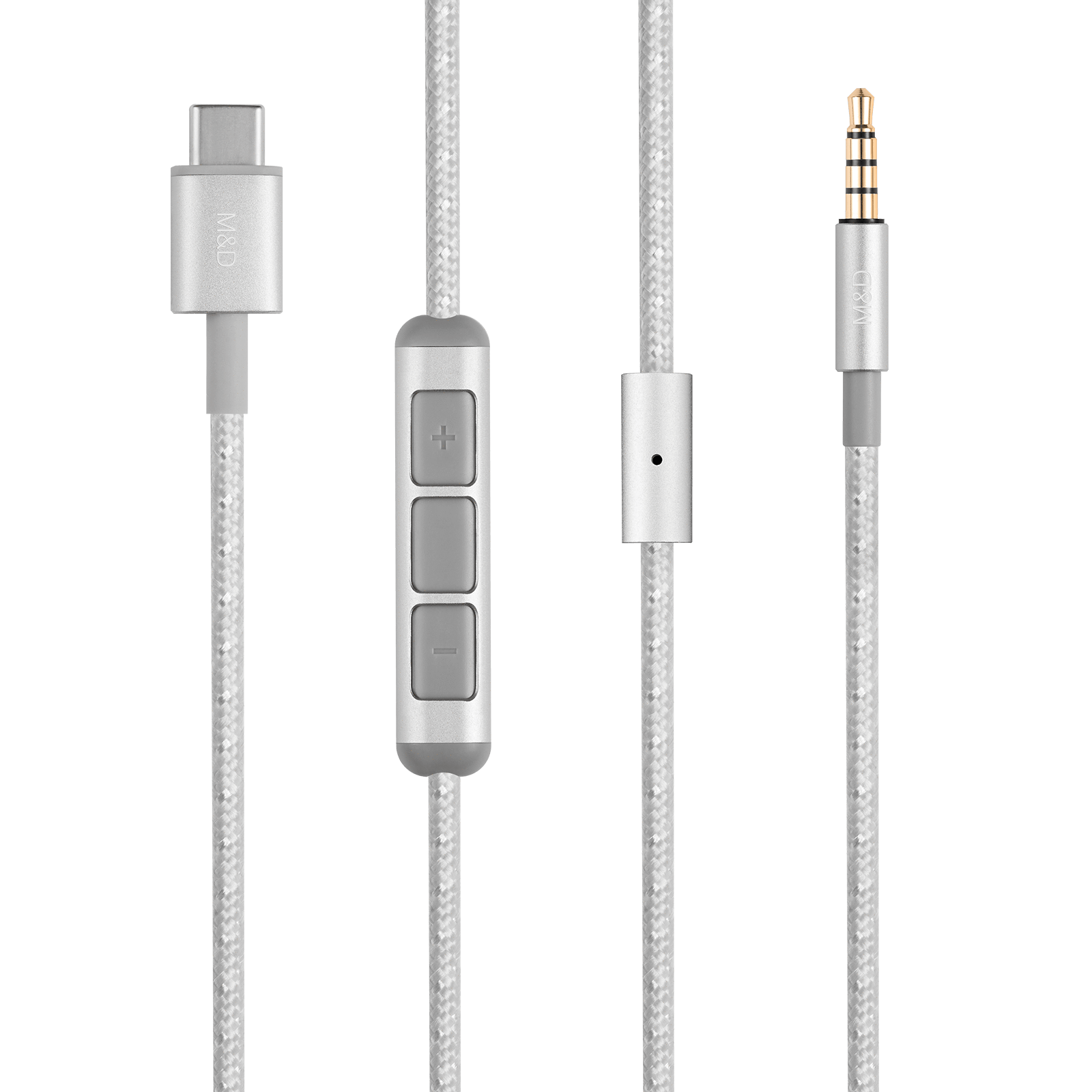

Laughter and conversation drift from the end of the carriage. The disembodied, tinny voice of the train driver vents from small speakers by the door, as a long bridge suspended over the river glides past my window. The low, constant groan of the engines is matched by a high-pitched whine of air conditioning units overhead. A table vibrates aggressively to my left, rattling the thoughts in my head. I open my suitcase, and draw my pair of Master & Dynamic headphones from their canvas bag. The arched leather band is soft in my grip, the aluminium details smooth against my fingertips. It feels solid and durable, but no weightier than the set of keys jingling in my pocket. I place the memory foam ear pads, surrounded in lambskin, over my ears. Instantly the carriage cacophony shrinks to a distance, as if separated by a body of water. I feel for the active noise cancelling switch on the side of the headphones, and flick. The low groans and murmurs disappear, the ambient hums and whines sucked into a vacuum. I sit in this way, in silence; my eyes shut, my mind quiet.

I try to visualise the noise-cancelling MW65 headphones’ inner workings: the hidden microphone array’s constant monitoring of background noise; the circuitry’s translation of these sounds into signals; and equal signals, emitted out of phase to those received, resulting in the opposing soundwaves cancelling each other out in perfect, oscillating collisions. It is a precise silence.

As I gaze at the opposite riverbank, undulating like a waveform above the light grey water, I consider which song I will choose to test these headphones for the first time. David Byrne of Talking Heads, in How Music Works, writes that the creation of all music is subconsciously shaped by the context in which it will be performed. Medieval classical music, with its held notes, simple harmonies, and slow movements, fits perfectly with the long reverberations of a Gothic cathedral. The more embellished and detailed music of Mozart could be well appreciated in the intimate parlours and private halls of his Viennese patrons. Pop music, in all its myriad forms, is often driven by percussive sounds and syncopated grooves. Distinct and effective when performed in small clubs, or funnelled through the powerful and sophisticated sound systems that amplify it across large venues, the same music could be a tumultuous mess in the natural acoustics of a Gothic cathedral.

What about this setting? Sitting on a train, immersed in a sonic void; ready to be filled entirely with pure sound, uninterrupted by the outside world; each tiny detail whispered directly in my ear. An inhaled breath, the rasp of fingers across a guitar string, the slightest, final reverberations of a decaying note. This is a unique musical context.