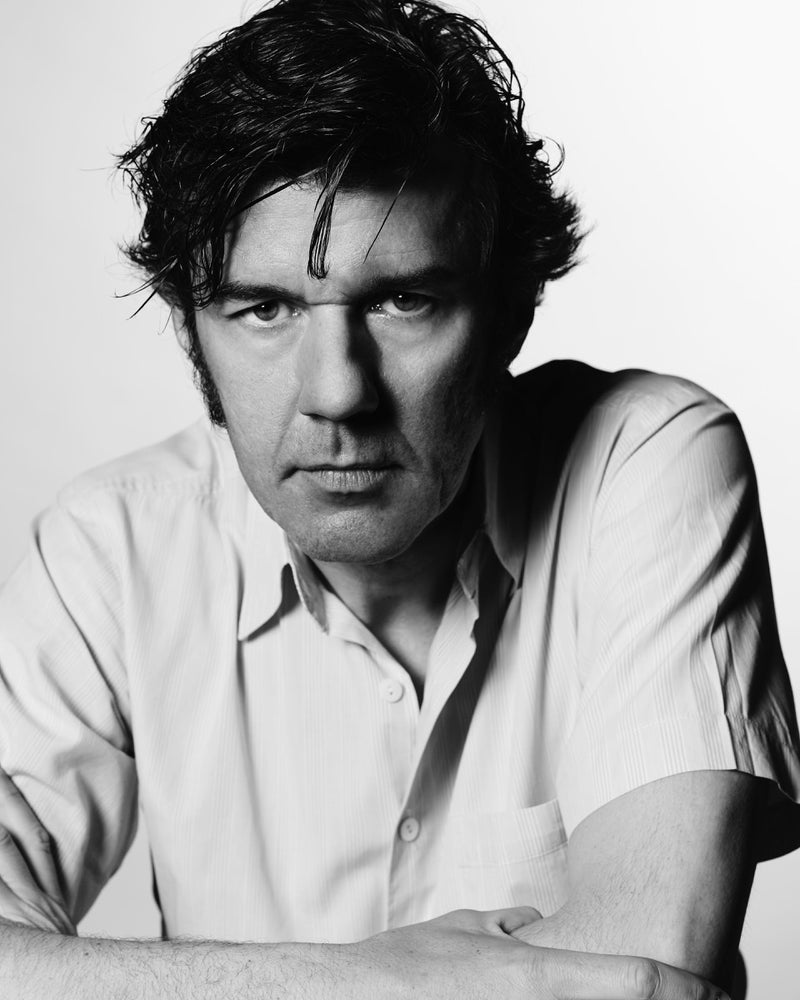

Lee Quiñones was one of the first artists to gain recognition during the peak of the New York City street art scene. The Puerto Rican-born, New York-based artist achieved acclaim in the 1970s for covering entire subway cars with provocative socio-political content and intricate composition. Surrounded by the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, Quiñones was one of the early core members of the graffiti group the Fabulous 5, and later brought Fab 5 Freddy (Fred Brathwaite) into the group. Over the next decade, he painted over 100 whole subway cars throughout the MTA system, then shifted to a studio-based practice. The 10,000 spoke to Quiñones on his meteoric rise in the art world, his moniker, and how music impacts his practice.

What made you take up graffiti and street art in the 1970s?

I’ve been a painter all my life. Since I was a child, I was always drawing and fascinated with visual arts, cinematography and film. I was coming out of a void of not creating for a few years when I discovered the colorful explosions happening on the trains, the pieces of work rolling in and out of my peripheral. That view on its own was inviting enough and I knew I wanted to join in on the collaboration of street art. We were all individual artists - part of a collective - it was a group mentality that turned out to be the largest art movement of all time.

How did you choose your moniker “LEE”?

The moniker is my middle name because I hated my first name. In this particular movement, names are interesting because there are two sides to the fence. Names tend to be a little narcissistic, especially when you are writing it over and over again. I picked “LEE” because it was short, so you can apply it quickly. It was a challenge to work with a name that had two of the same letters in it, which is one of the hardest things to do when you’re constructing a name (even if it’s just twice). My name then became a secondary objective in my paintings because I wanted to create a visual narrative. I didn’t want my name to be the only fundamental thing that existed in my work. The work had to have a storyboard to it, as well as color and a temperature reading.

Why did you choose subway cars as your original canvas?

Subway cars were always there, they were accessible. Back in the day it was only a nickel or so for a subway token. The subway cars and riders were inviting, they were considered the blood of the city. The kinetic energy of the city was through those subways. The trains ran from one extreme part of the city to another so it was a great way to have your work in motion, being seen by all different groups of people. It became the “Instagram of the day” because you would paint a vivid piece of work on the train and it would be seen by a stranger on the other side of town. Suddenly, those strangers knew who you were just by virtue of seeing the persona in the work, by seeing the character in the work itself.

How do you deal with critics who viewed your early work as “vandalism” or “tagging” when you were pursuing your form of artistic expression?

“Tagging” is a very loaded word, it’s not well thought out. People would say these young, artistic individuals are misdirected youth, that they’re hellbent on going against society and breaking into municipalities just for the fun of it. The truth is however, the city was totally upside down in the 1970s when I started painting in that fashion. “DROP DEAD” was the famous headline after the president at that time denied the city a federal bailout when it was in a total fiscal and identity crisis. We were toward the end of the Vietnam War and we needed to find a new voice. Young individuals needed to find a sense of community because there were not many great options for us out there. I was 13 years old in 1974 when I discovered the outlet and created enough noise in the city to be seen in a place like New York that’s constantly changing. We rolled up our sleeves, created something from nothing and staked our claim. When terms like “tagging” and “vandalism” come into effect it makes it look like it was very minimal and miniscule, that it’s just a one-time act of vandalism but it really wasn’t at all. There were so many bad options left on the table for us by society, so the young decided to take the flag and make our own stamp of approval within ourselves. In any artistic movement the first mobile that starts to turn is always turbulent and sometimes controversial. Then, 30-40 years down the line, it’s embraced and celebrated.

You’ve been hailed as the “single most influential artist to emerge from the New York City subway art movement.” What does that title mean to you?”

Only from afar can you actually define what things meant. I had done some very unprecedented masterpieces back in the day that people are still awed by. They’re shocked that I, along with the crew I painted with called the “Fabulous 5ive,” successfully covered a whole, moving subway train (10 cars). There were only five of us, a quintet of colorful misfits; but, we created that to create a sense that this was even bigger than all of us. I went on to create the first top-to-bottom handball court mural, Howard the Duck (1978), in my old neighborhood on the Lower East Side, which positively changed the conversation surrounding this movement of what it was and where it was going. It was monumental and I didn’t realize it at that time. I did know I was doing something beyond other people’s scope that would change the course of art history; but, at the time, I thought it was another challenge or card in my chest.

Speaking of art history, your work seemed ahead of the graffiti and Street Art curve that later boomed in the 1980s.

The [handball] walls I created actually influenced Keith Haring’s Crack is Wack (1986) wall in Harlem River Park. Haring asked me, “Lee, how did you paint those walls?” It was at that time that I realized I had done something that had never been done before. He was so amazed that I had gone to those great lengths, heights and vulnerable situations to create such a miracle above ground. I had arrived as an artist and I took that leap of faith to either fail or succeed, which changed this movement’s course. Fab 5 Freddy and I were among the first graffiti artists to travel to Europe for an exhibition of graffiti-based works in a gallery in 1979 when I was 19-years-old. For the show, Fab 5 Freddy, Jean-Michel Basquiat and myself were sharing a studio generously given to us by the British visual and conceptual artist Stan Peskett. He had this huge loft down on the bottom of Canal St. and West Side Highway, but it was the first time we actually had a sense of a studio environment and practice. In the studio, Basquat created smaller works and postcards, but he got his first hand on a crash course on how we made that transition of going from a mentality and the temperature of the subways to a studio practice and then to a presentation in a gallery. From there, either the wheels came off the cart or the cart went to places we never imagined—the rest is history as they say.

Is music integral to your process? Who or what do you listen to while completing a new artwork?

Without music, I don’t know if I can even find a way to investigate things in life. I think I speak for many of my peers and artists, in general, that listening to music is to mine something from it and go with it as a result. Music is not about helping me with ideas, but rather, it gives me access to vibes because vibes are more genuine than ideas. Ideas are like those “eureka” moments that we create to make a statement or, in some ways, be pretentious. When art comes from vibes you can feel it from the inside out. That may come in color. Color can set a mood and that mood, through music, can turn into something. I listen to all genres of music. When I was painting, I listened to a lot of rock and soft rock. I would go from Elton John, who is one of my favorite composers, to Billy Joel and ended up listening to Blue Oyster Cult and then I discovered U2 and Debbie Harry. I also go back and forth with James Brown and Isaac Hayes. When I was going into dangerous environments such as a subway tunnel, I shifted to composers and film scores like Lalo Schifrin, John Williams and a host of other characters that created this atmospheric music that made me feel comfortable in my skin.

Can you recall a specific time where your art was impacted by music?

A few years ago, I was at a club in Chelsea and bumped into Debbie Harry, who I hadn’t seen in years. She was in a trance, deep sea diving for a vibe. I looked at her, but she looked deep in thought, almost mining herself and I didn’t want to disturb her. It was like two ships passing in the night. When I left the club, I got on the subway and the car was empty except for me and a young woman across from me sobbing. I was paralyzed because I didn’t know what to say or do. It was just me and her in that car like right out of a dream. All of a sudden, the car began to fill up and two stops later, she got off. I’m looking at her and I’m so mad at myself because I felt I should have said something comforting. There was despair in front of me, then suddenly the train was packed with people. I’m in the studio the next day painting regions of color and listening to Stephen Sondheim’s "Send in the Clowns." When you hear that song, you can feel the vibe I felt that whole night. The song became the title of my portrait of Debbie turning into Madonna in an empty subway car holding a switchblade with a “don’t f*** with me” look. I gave empowerment to that young woman in the painting because I felt so shameful that I couldn’t help her. Maybe I was there only to investigate and be a fly on the wall for a reason I cannot explain. Send in the Clowns (2009) is based on that powerful song and it is kind of like a symphony of sympathy—it’s simply what I felt at the time.

To learn more about Lee Quiñones and his work, visit www.leequinones.com

Part1.jpg?v=0)

Part1.jpg?v=0)